A shot of a road version of the BB-7 Avid mechanical disk brake - his example is nice and clean, rather than using an image of mine ~

Even this very detailed description and advice does not cover the problem I had with BB-7 brake set up that neither the bike store that sold me the bike with these brakes nor mechanics at my LBS were able to identify.

I bought a Traitor Ruben in the summer of 2009. I generally ride it to commute to work when the weather looks like rain or is otherwise crummy - otherwise I ride a more pleasant (in my view) road bike. One of the main advantages (if not the main advantage) is that in rain the mechanical disk brakes, Avid BB-7s, have no noticable drop-off in performance that you have with rim brakes. The problem can be that adjusting these brakes to perform reasonably whether raining or not can take some effort.

The many-step process described by the blogger above leaves out the problem I was eventually able to correct that seriously lowered the BB-7s' performance for me. The problem I had stemmed from incorrect setup by the store that sold the bike to me. (Or perhaps by the company that produced it, I suppose.)

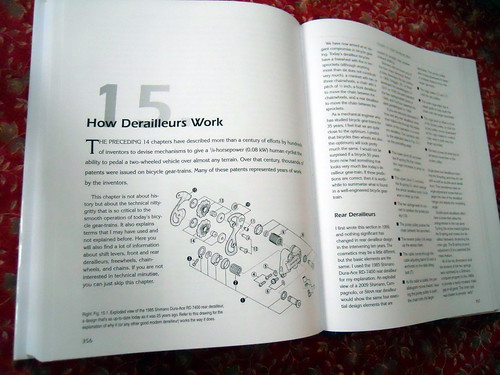

Two disk brake pads not yet mounted in their spring are at left, two mounted in spring (they look like a tiny waffle iron) are at right.

In order to operate properly, the brake pads, pressed together with their spring into a kind of brake pad-sandwich, need to be inserted fully into the caliper slot. Each pad has two small "ears" that are supposed to fit into a metal clip that is inserted into the caliper from the opposite side from where the brake pads slide in. As it turns out, this clip is quite strong and getting the pad "ears" to fully engage with the clip takes a bit of force - and if you convince yourself that they are fully seated (it isn't readily apparent whether they are or not by visual inspection) then the brake pads don't lay flat against the pistons but instead are sort of balanced on top of two pins that are in the middle of each of the pistons. When the pads click into the clip properly the pin on the piston will seat in a slot in the back of each pad and hold them in the right place. (Yes, hold them in the right place in addition to the clips - the clips that seem to work more to keep them out of the right place.)

What this means is that instead of having the pads solidly pressing against the pistons on each side, they are wobbling around, made parallel to the disk only by the tiny spring that is intended simply to push them apart. It is possible for an otherwise sensible bike mechanic to perform the usual setup process and miss that the pads aren't fully inserted. When the pad aren't sitting fully against the pistons, the pads wear at a highly accelerated rate and the performance is poor, although it isn't so poor as to indicate the serious problem you actually have in this situation.

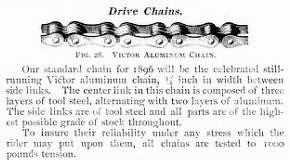

Here you can see the slot where the clip inserts, just to the left of the red adjustment dial that is visible

My simple solution that Avid would doubtlessly not like was simply to take the clips out and insert the pads fully so they were in the right place and mounted on the pistons properly, and leave it at that. The little posts on the pistons are inserted into slots in the back of the pads and keep them in place just fine, it seems. I did try to insert the clips after the pads were in the right place, but that didn't work, so I just left them off. I had a BB-7 on a bike (just on the front fork) that I gave away that was an older model (before this "mtn" and "rd" distinction appeared) and I don't think it even had this clip, so I decided that I couldn't see any reason why if the pads were properly inserted that the clip was necessary. With the pads fully inserted it has been much easier to adjust the brakes to achieve decent performance (and pad wear). I have been riding like this for 500 miles or so, no problem.

So, how did I discover that I had this problem that mechanics didn't see? I had a separate problem with the rear wheel of this bike and had it rebuilt when several spokes blew (described in this post) so I had my LBS that rebuild the wheel and when they put it back on the bike the guy neglected to tighten the skewer enough and silly me didn't check his work so I was riding in a downpour and the rear wheel popped out, yanking the brake bads and spring out. (Luckily I did not fall, although I was mighty surprised.) When I looked closely at the wear on this set of pads, I realized something other than simple adjustment was wrong. I bought new pads for front and back and realized upon more thoughtful examination that the front pads weren't fully inserted (and presumed this had been the problem with the rear one as well). Geez!

I guess the sense that disk brakes are a little more complicated to adjust masked the more serious problem since I assumed that the bike store had set the things up properly in the first place. At one point, tired of making constant adjustments, I stopped at the other good LBS and a mechanic performed his version of the setup but while it seemed OK for a while, it was back to poor performance in a day or so. Anyway, I guess I learned something - perhaps even several things.

In addition to my disappointment with professional bike mechanics in this (which isn't really that great; this isn't brain surgery) I think the Avid instructions supplied are part of the problem - they are pretty poor. The Avid PDF manual (that is the same as what is delivered with the brakes) states that pads should "click" into place but the critical importance of seating the pads in the clip isn't mentioned specifically as the necessary requirement. The two pages have the same information in nine languages, so the degree of clarity in any particular language is proportionally reduced. The steps to take are described, but not much "why this step is important" sort of info.